Remember, Remember, The 5th of November...

Guy Who? Meet Robert Catesby: the real mastermind behind the Gunpowder Plot.

David@PlanPackGo.blog

11/5/20256 min read

Okay, we know this is usually a travel-focused blogsite, packed with lots of great information and snippets for holidaymakers and travelers, but today is a little different. It's bonfire night here in the UK - Guy Fawkes night if you prefer - and David, our resident history buff, just couldn't help himself. Think of this as his Simon Schama or David Starkey 'moment.'

So here it is. Our own brief retelling of the infamous 'Gunpowder Plot' incident, England, in the year 1605. And why the scoundrel Guy Fawkes was really just a bit-part actor. Enjoy this, and let us know what you think.

And remember, remember - this story would make the basis for a great historical road trip in the UK!

********

Every year on the 5th of November, as fireworks light up the British sky and bonfires crackle across the nation, we remember the Gunpowder Plot. We burn effigies of a cloaked figure with a pointy hat and a sinister moustache, a man whose name has become synonymous with treason: Guy Fawkes. But what if I told you that for over 400 years, we’ve been focusing on the wrong man? What if the figure we should be discussing, the true architect of this audacious act of terrorism, was a charismatic, wealthy, and dangerously devout gentleman named Robert Catesby?

As a historian by nature, I like to look beyond the popular narrative, to sift through the ashes of time and uncover the real story. And the real story of the Gunpowder Plot is not about the hired muscle caught with the matches; it’s a tragic, gripping tale of a charismatic leader who inspired a band of brothers to risk everything for their faith, a man who was the heart, soul, and strategic genius behind the entire conspiracy.

The Man Who Would Be Kingmaker: Who Was Robert Catesby?

Born in 1572 into a prominent Catholic family in Warwickshire, Robert Catesby was a man of contradictions. He was, by all accounts, magnetic. Standing over six feet tall, he was described as having an “exceedingly noble and expressive” countenance, with manners that were “peculiarly attractive and imposing.” He was a man who commanded respect in any room he entered, a natural leader who, as his friend Father John Gerard noted, was “respected in all companies of such as are counted there swordsmen or men of action.”

Yet, beneath this charming exterior was a core of hardened steel, forged in the fires of religious persecution. Catesby’s family, like many English Catholics, had suffered immensely under the Protestant rule of Queen Elizabeth I. His own father had been imprisoned for his faith. Robert himself was educated at Oxford but left without a degree, presumably to avoid swearing the Oath of Supremacy, which would have compromised his Catholic beliefs. He was a man who had seen his world shrink, his rights curtailed, and his faith driven underground.

His moment of radicalization likely came after the failed Essex Rebellion in 1601. Catesby, ever the man of action, had joined the uprising, hoping it might lead to a more tolerant monarch. Instead, it led to his capture, a hefty fine of 4,000 marks (a fortune at the time), and the forced sale of his beloved family estate at Chastleton. This was a turning point. Stripped of his wealth and status, Catesby’s resentment hardened into a dangerous resolve. When the Protestant King James I ascended the throne in 1603 and failed to deliver the religious tolerance many Catholics had prayed for, Catesby’s patience finally snapped. He decided that if the system would not bend, he would break it.

A Band of Brothers: Forging the Conspiracy

Catesby’s genius lay not in handling explosives, but in handling men. He possessed an “irresistible influence,” and he used it to assemble a team of loyal, desperate, and equally devout Catholic gentlemen. This was not a gang of hired thugs; it was a brotherhood, bound by blood, marriage, and a shared sense of righteous fury.

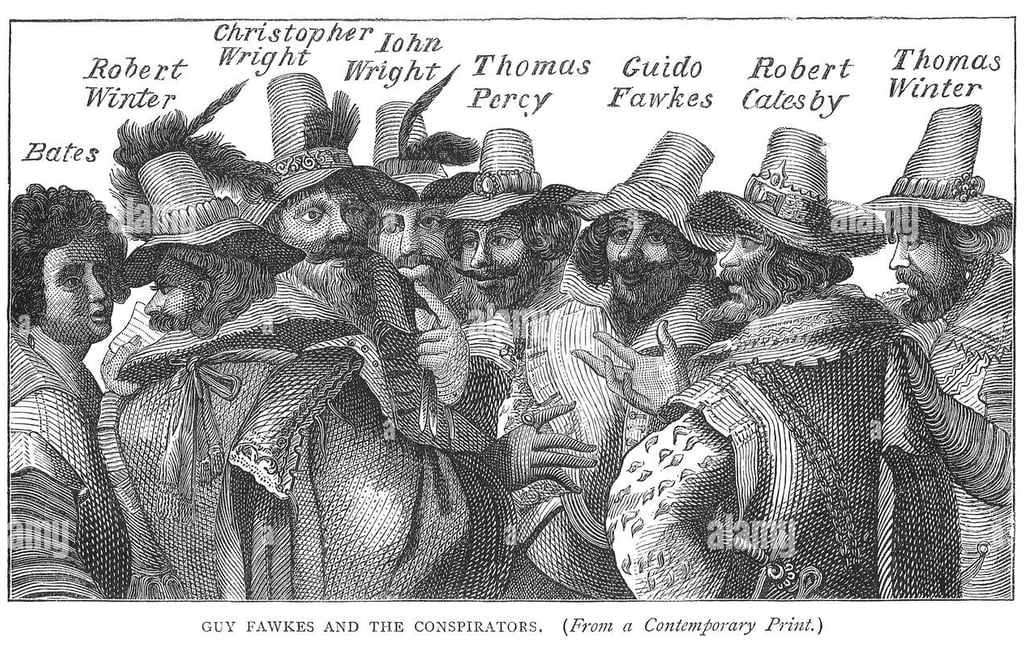

He started with his inner circle. In early 1604, he summoned his cousin, Thomas Wintour, a scholarly soldier who had fought for England but converted to Catholicism. He brought in John Wright, a renowned swordsman and one of Catesby’s oldest friends. Then came Thomas Percy, a volatile and angry man, a relative of the powerful Earl of Northumberland, who had once threatened to kill King James himself. Catesby calmed him, famously saying, “No, no, Tom, thou shalt not venture to small purpose, but if thou wilt be a traitor thou shalt be to some great advantage.”

And then came the man we all remember: Guy ‘Guido’ Fawkes. Fawkes was not a close friend or a family member. He was a professional, a soldier with ten years of military experience fighting for Catholic Spain in the Netherlands. He was recruited specifically for his expertise with gunpowder and his nerves of steel. He was the specialist, the technician. Catesby was the visionary, the CEO of this deadly enterprise.

Over the next year, the circle expanded to thirteen. It included brothers, cousins, and trusted friends like Ambrose Rookwood, who later said he “loved and respected him [Catesby] as his own life.” Catesby’s charisma was the glue that held them all together. He persuaded them that this act of “tyrannicide,” this “decapitation strike” against a heretical government, was not a sin but a sacred duty. He was their commander, their confessor, and their inspiration.

The Plot: A Spectacular Plan, A Spectacular Failure

The plan was as simple as it was audacious: blow the House of Lords to smithereens during the State Opening of Parliament on the 5th of November, 1605. In one fiery blast, they would eliminate the King, the royal family, and the entire Protestant ruling class. In the ensuing chaos, they would launch a popular uprising in the Midlands and install King James’s nine-year-old daughter, Princess Elizabeth, on the throne as a puppet Catholic queen.

They rented a cellar directly beneath the House of Lords and, under the cover of darkness, Fawkes and his associates smuggled in 36 barrels of gunpowder – enough, it was later calculated, to reduce the entire building to rubble and cause devastation for a third of a mile in every direction.

But as the date drew near, a fatal flaw emerged: conscience. Some of the conspirators grew worried about the Catholic lords who would be present at the State Opening. Would they be killed alongside their Protestant enemies? Catesby was ruthless. He argued that the innocent would have to perish with the guilty for the greater good. But someone’s nerve broke.

On the 26th of October, an anonymous letter was sent to the Catholic Lord Monteagle, warning him to stay away from Parliament. The letter, now one of the most famous in English history, was a masterpiece of ambiguity, but its message was clear enough. Monteagle, terrified, showed it to the authorities. The plot was blown.

The Final Act: A Last Stand and a Gruesome End

On the night of the 4th of November, just hours before the planned explosion, a search party stormed the cellars. They found a man calling himself ‘John Johnson’ guarding a large pile of firewood. It was, of course, Guy Fawkes. The game was up.

As news of Fawkes’s arrest spread, the remaining plotters fled London in a desperate, panicked ride to the Midlands. Catesby, ever the leader, tried to rally his dwindling forces, but the planned uprising never materialized. The fugitives were now outlaws, hunted men. Their flight ended on the 8th of November at Holbeche House in Staffordshire.

Tired, wet, and desperate, they made a foolish mistake. They spread some of their damp gunpowder in front of the fire to dry. A stray spark ignited it, and the resulting flash-fire engulfed Catesby, Ambrose Rookwood, and John Grant. Catesby was scorched but survived, his resolve unbroken.

Surrounded by a 200-strong sheriff’s posse, Catesby knew his end was near. He refused to be taken alive. As the posse stormed the house, Catesby, along with Thomas Percy and the Wright brothers, stood their ground. In his final moments, Catesby was seen to kiss the gold crucifix he wore around his neck, declaring he had given everything “for the honour of the Cross.” He and Percy were struck down by a single musket ball, a fittingly dramatic end for two men who had lived so boldly. Catesby was later found dead inside the house, clutching a picture of the Virgin Mary.

His death, however, was not the end of his punishment. In a grim warning to other would-be traitors, his body was exhumed, posthumously beheaded, and his head was placed on a spike outside the Houses of Parliament – the very building he had schemed to destroy.

And what of Guy Fawkes? He was taken to the Tower of London and subjected to brutal torture. Though he initially resisted, he eventually broke and confessed, revealing the names of his co-conspirators. On the 31st of January, 1606, he was brought to the scaffold to be hanged, drawn, and quartered – a truly horrific fate. But Fawkes had one last act of defiance. Weakened by torture, he managed to climb the ladder to the gallows and jump, breaking his own neck. He cheated the executioner of his final, gruesome task.

The Legacy: Why We Remember Fawkes

So why, on this night of all nights, do we burn an effigy of Guy Fawkes and not Robert Catesby? The answer lies in the simple, brutal facts of history. Fawkes was the one caught in the act, the man with his hand on the fuse. He became the face of the plot, the physical embodiment of the treason. Catesby, the charismatic leader and brilliant strategist, died in a chaotic firefight far from the public eye. His story was more complex, his end less symbolic.

But as we watch the fireworks burst and the bonfires blaze, it’s worth remembering the true story. The Gunpowder Plot was not the work of a lone fanatic, but a carefully planned conspiracy driven by a man of extraordinary influence and unwavering conviction. It’s a story of faith, fanaticism, and failure, a story of a leader who inspired others to follow him to their deaths. It is, in the end, the story of Robert Catesby.

Info:

email:

Message us:

david@planpackgo.blog

© 2025. All rights reserved.

planpackgo.blog is a wholly-owned

brand by DMH Media Hub